This week, we discussed 4 considerations for the integration of urban ecology in urban planning so that biodiversity and ecosystem services in cities could be conserved:

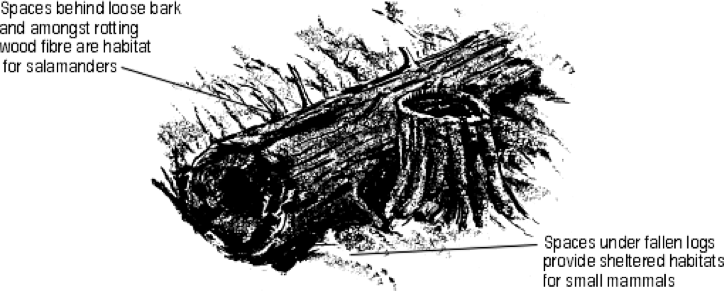

- Protecting key urban biophysical assets that have been shown to be particularly valuable to conservation — these sites are often overlooked or frowned upon in urban settings, such as fallen logs (see Figure 1)

- Creating greenways to promote connectivity — networks of land and water that are designed with various multifunctional purposes spanning ecological and recreational uses

- making use of small green spaces (managing private gardens)

- promoting green architecture

For this week’s learning diary, however, I want to focus on the first 2 considerations and the question of whether various urban planning initiatives serve more purpose for humans or wildlife. In other words, how much of city planning is motivated by the desire to conserve biodiversity? Is it something that the public and city planners have deemed intrinsically valuable, or is it considered secondary to aesthetic or economic concerns?

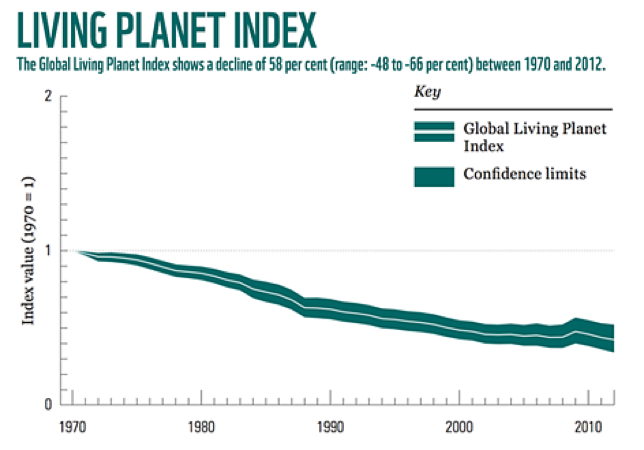

This presents an opportunity for me to connect this week’s learning to last week’s discussion of socio-economic inequality and its influence on the political acceptability of environmental preoccupations. Research conducted by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) shows that biodiversity preservation (as measured by WWF’s Living Planet Index) has fallen 30% globally (see figure 2) — but strikingly, developed countries have actually improved their Index; most of this drop comes from low-income countries, where motivations to preserve biodiversity are low on the list of pressing issues. Richer countries not only have the resources to preserve their biodiversity, but also the ability to “exploit the biodiversity of natural capital-rich but income deprived countries”.

Thus, Singapore’s many initiatives — such as the building of greenways and park connectors — must be seen in the light of the nation’s wealth; such initiatives are only possible and indeed popular because of available resources. Furthermore, policies concerning greenways are still largely directed towards human recreation, and tied to economic benefits.

This week’s topic — the integration of urban ecology in city design — and considerations of biophysical assets and greenways provided a platform for me to think about the weight of biodiversity conservation in Singapore’s planning policies. I discovered the influence of a nation’s wealth in its stance on protecting biodiversity, again pointing to the recurrent theme of socio-economic inequality’s role in determining environmental values. Meanwhile, Singapore continues to be a global leader in incorporating urban greenery in the city landscape — a position that is well-deserved, but one that must be caveated with concerns for decreasing conservation sites that are considered to lie not within, but outside urban spaces.

- Bartels, R., Dell, J. D., Knight, R. L., & Schaefer, G. (1985). Dead and down woody material. In Brown op cit. pp. 171-186.

- WWF, The Living Planet Report 2012, WWF.

- Laurent E. (2014). Inequality as Pollution, Pollution as Inequality: The Social-Ecological Nexus. Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality.

- Theng M, Sivasothi N. (2016). The Smooth-Coated Otter Lutrogale perspicillata (Mammalia: Mustelidae) in Singapore: Establishment and Expansion in Natural and Semi-Urban Environments. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 33: 37–49.